"After the 2025 bleaching: A Reef in Crisis" - Check our blog for more information and subscribe for project updates, news and events!

After the 2025 bleaching: A Reef in Crisis

6/11/20256 min read

The sobering truth

It began with silence...

Just a few months ago, we sounded the alarm: the reefs of Mauritius were in distress, their vibrant colours fading as a mass coral bleaching event took hold. It was a stark warning from the ocean itself, a signal of rising stress beneath the waves. At the time, there was still hope: that with the return of cooler waters, the corals might bounce back, that nature’s resilience would prevail.

But now, having returned to those same waters for our post-bleaching surveys, we are met with a sobering truth. What we witnessed was not just a loss of colour, but a loss of life. Entire sections of reef, once thriving and teeming with marine creatures, now lie barren, suffocating from algal growth on dead coral skeleton. The reefs did not fully recover...They died...

Post-bleaching surveys

In June 2025, as sea temperatures finally began to cool (<27°C), we returned to our monitoring sites with cautious optimism, hopeful that the corals, once bleached by the unprecedented heatwave, might have begun their path to recovery. Equipped with datasheets, underwater cameras, and a quiet sense of anticipation, our team revisited key stations across Le Morne, La Prairie, Bel Ombre, Beau Champ, St Martin, and St Félix.

What we found was devastating...

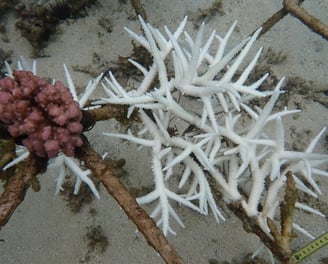

The once-thriving reefs, bursting with colour, movement, and life, had been reduced to skeletal remnants, many smothered by creeping layers of turf algae. Whole colonies of Acropora, stood ghost-like, devoid of their living polyps. Some corals still clung to survival, but their bleached, fluorescent whiteness told a story of ongoing struggle.

The damage was profound. In several locations, over 40–50% of previously healthy coral colonies had succumbed, unable to recover from the bleaching stress. But it wasn't just the corals that were gone. Life across the reef had thinned. Fewer fish darted through the reefscape and the crustaceans had all but vanished. The biodiversity that once danced through the coral crevices was now a memory. Even the sea anemones (Heteractis magnifica), once pulsating with life, now stood bleached, white as snow, their tentacles ghostly and still. The vibrant anemonefish (Amphiprion chrysogaster) that once darted between them, offering flashes of orange and black, were nowhere to be seen. These charismatic reef dwellers, endemic to the Mascarene Islands, had vanished.

Nemo had left home and with it, we are losing an overlooked treasure of our marine heritage.

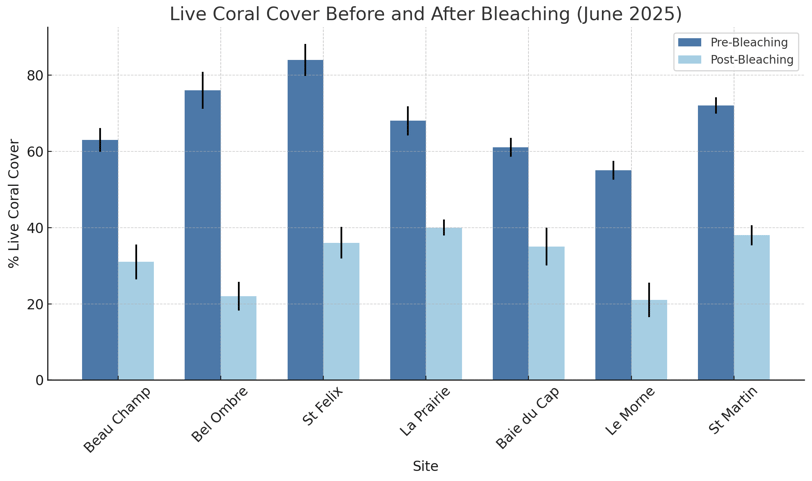

Worst of all, our transect surveys revealed an even grimmer reality, one that confirmed what our eyes had already seen:

Coral mortality: At several sites, live coral cover had plummeted, falling from over 60% to less than 40% in a matter of months.

Algal overgrowth: The once-living reef structure was being rapidly colonised by turf algae and cyanobacteria, smothering what remained of the dead coral skeletons.

Fish abundance: Herbivorous and reef-associated fish populations had declined sharply, their absence echoing across the silent reefscape.

Invertebrates: Sea urchins which once populated these reef ecosystems were now alarmingly scarce, absent from zones they once dominated.

These numbers are more than data points, they are indicators of a collapsing ecosystem. Without immediate action, the chain reaction could unravel decades of recovery and conservation work.

A glimmer of hope at St Felix

As we dove into the heart of our restoration efforts at St Felix, we expected to find resilience but were unsettled to discover that even these carefully tended corals bore the scars of the extreme bleaching event. Both our nurseries and spider-frame coral gardens faced severe bleaching: around 70 % of corals had bleached by the end of March 2025. The same was observed within our VMCA site, where more than 70% of the coral colonies (especially from the genus Acropora had bleached).

Yet, post-bleaching surveys in June 2025 revealed divergent fates:

In our spider frame coral gardens:

30 % mortality of previously healthy colonies were observed.

The remaining 40 % remained bleached and precariously clinging to life.

In our coral nurseries:

40 % of corals died, predominantly branching species such as Acropora muricata and tabular Acropora cytherea.

Remarkably, however, colonies of Acropora selago, various Pocillopora, and Porites not only survived but have fully recovered

In the VMCA:

Over 50% of naturally occuring (wild) coral colonies of Acropora muricata and tabular Acropora cytherea had died within the VMCA. These species bleached over 80% in March 2025.

A tale of two reefs: Wild vs. Nurtured Corals!

Among the most striking revelations of our post-bleaching surveys was the contrast between wild coral colonies and those we had carefully nurtured in our nurseries and coral gardens at St Felix. While both groups experienced widespread bleaching, their survival trajectories diverged dramatically.

In our spider-frame gardens and nurseries, many corals, though visibly bleached, suffered significantly lower mortality rates than their wild counterparts. What made these cultivated colonies more resilient?

The answer may lie in their origin.

These were not pristine, untouched corals which were harvested from healthy colonies. They were Corals of Opportunity (COPs), fragments broken off from parent colonies by storms, wave action, or mechanical disturbance. Left adrift on the reef, these fragments would likely have been smothered in sediment and lost. But instead, we salvaged, acclimatised, and raised them in our nursery environments, giving them a second chance.

Ironically, it may be this early hardship that built their strength.

Research suggests that repeated exposure to stress, such as physical damage, handling during collection, and environmental shifts during nursery acclimation, can trigger adaptive physiological responses in corals. These include:

Physiological acclimatisation: gradual changes in coral phenotype that enhance tolerance to future thermal stress

Symbiont shuffling: the ability to host more heat-tolerant strains of symbiotic algae (e.g., clade D), which can offer short- or long-term thermal resilience

These processes have been documented in both laboratory experiments and natural reef environments around the world. It is possible that our nursery-grown corals, having already faced and survived earlier stress, and this has helped them better withstand the intense heat stress of the 2025 bleaching event.

In essence, while many wild colonies succumbed, our coral gardens told a story of hope: that resilience can be cultivated, and that restoration is not only about saving coral but it’s about preparing them for the battles ahead.

Call to Action

The ocean has spoken. And now, we must act.

At Coral Garden Conservation, we want to double our efforts to:

Scale up coral propagation and restoration through creation of nurseries and gardens.

Support community-led reef stewardship programs.

Advocate for stronger climate-resilience policies and reef protections.

But we cannot do it alone. Whether you are a policymaker, a student, a diver, or a concerned global citizen, you have a role to play. The reef’s story is not finished - but its next chapter depends on what we choose to do now.

Stay informed, take action, and help us safeguard the future of our oceans. Follow CGC for more updates and ways to get involved in marine conservation.

Coral Garden Conservation

CGC © 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Disclaimer

Powered by Eco Marine Consultants Ltd