What are Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS)?

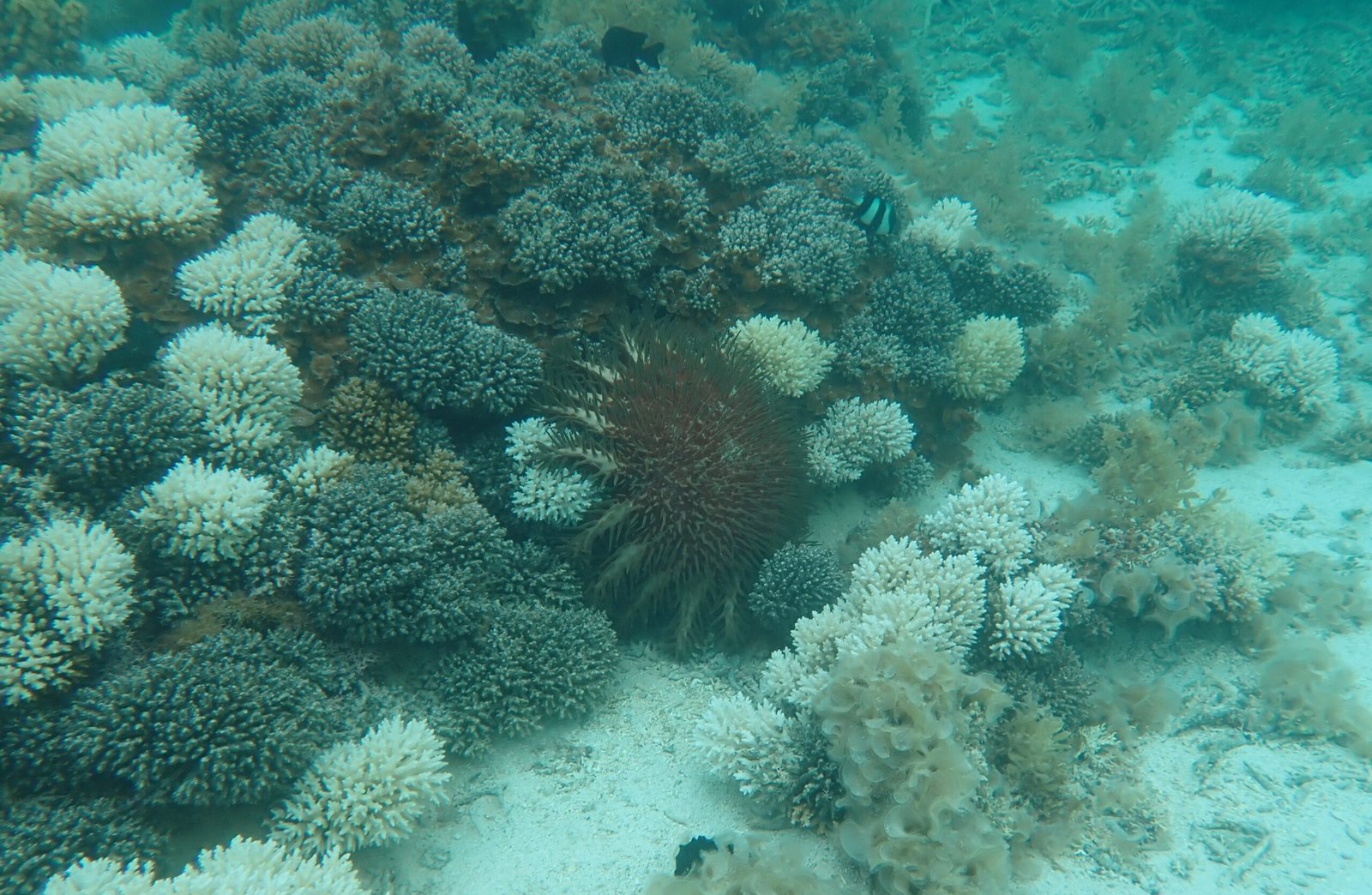

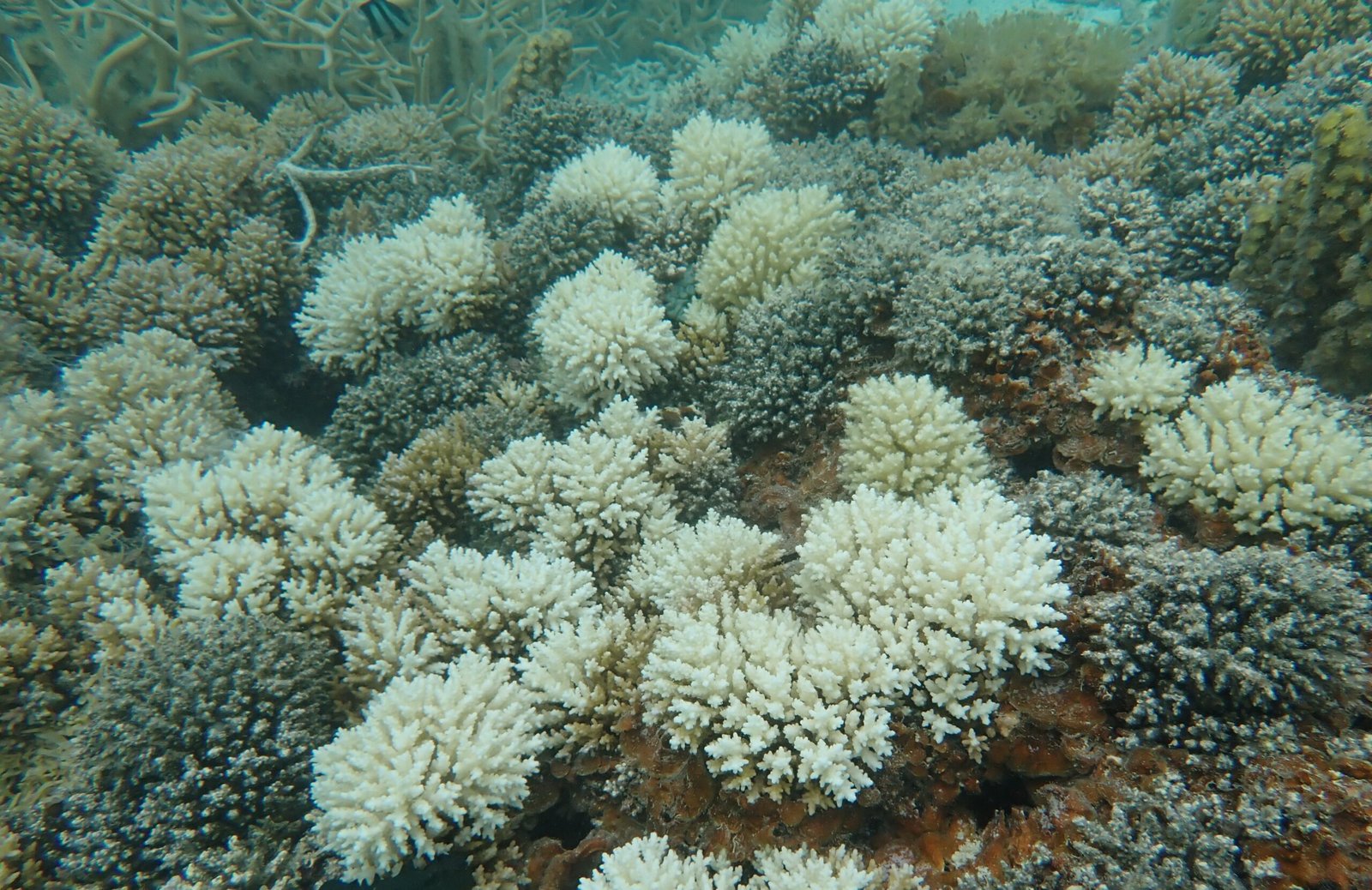

The Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS), scientifically known as Acanthaster spp., is a voracious predator of coral that inhabits tropical coral reefs across the Indo-Pacific. In controlled numbers, COTS can play a beneficial role within coral ecosystems by feeding on fast-growing coral species, such as Acropora spp., which allows slower-growing corals to establish, enhancing coral diversity. However, when COTS populations increase, a phenomenon known as an outbreak, they can severely damage coral reefs, often leading to extensive coral mortality, negatively affecting the whole ecosystem's health, biodiversity, and structure. Rapid increases of COTS populations can devastate a coral reef in a matter of months or even as short as one month.

COTS biology and ecology

COTS are distinguished by their multi-armed, spiny structure, with adult individuals typically spanning up to a metre in diameter, and possessing between 14 and 18 arms, though they may grow up to 21. They vary in colour, including shades of blue, purple, green, and yellow. They lifecycle starts with a planktonic larval phase, where they begin their benthic life as herbivores. However, as they reach their juvenile phase, with size of >8 mm diameter, they subsequent start their corallivorous stage by feeding on corals. Their feeding process involves extruding their stomachs over coral tissue, digesting it and leaving behind a bare white skeleton. COTS primarily consume stony corals, with a particular preference for branching and tabular corals from the genus Acropora. However, in the absence of preferred corals, COTS may feed on other coral species, sponges, and even algae, highlighting their adaptability in diet, which contributes to their resilience and impact on reef systems. Depending on geographical locations and reef system health, natural COTS densities may range from 1 to 15 individuals per hectare, under which reefs can recover from feeding damage. However, in an outbreak, COTS densities may exceed 15 or even 30 starfish per hectare, leading to rapid reef degradation as their feeding rates exceed coral growth and recovery rates. An individual COTS can consume up to 12 to 13 square meters of coral annually, with large-scale outbreaks resulting in the devastation of up to 90% of live coral cover in affected areas. The fast growth and large body size of COTS, rapid consumption of coral and their dietary flexibility as well as their ability to cover a large spatial extent of reefs make these sea stars the most destructive coral predator.

Causes of COTS outbreak

The causes of COTS outbreaks have long been a topic of debate. While natural factors such as temperature and salinity fluctuations are known to influence COTS populations, human activities have increasingly intensified conditions favourable to these outbreaks. Research hypotheses explaining COTS outbreaks primarily fall into two categories: one focusing on the larval (planktonic) stage—known as the "terrestrial runoff hypothesis"—and the other on adult (benthic) starfish, referred to as the "predator removal hypothesis".

The terrestrial runoff hypothesis

The causes of COTS outbreaks have long been a topic of debate. While natural factors such as temperature and salinity fluctuations are known to influence COTS populations, human activities have increasingly intensified conditions favourable to these outbreaks. Research hypotheses explaining COTS outbreaks primarily fall into two categories: one focusing on the larval (planktonic) stage—known as the "terrestrial runoff hypothesis"—and the other on adult (benthic) starfish, referred to as the "predator removal hypothesis".

The predator removal hypothesis

This hypothesis proposes that overfishing of key COTS predators, such as the Giant Triton or Triton trumpet snail (Charonia tritonis) and Titan Triggerfish (Balistoides viridescens), contributes to outbreaks. It is believed that the absence of these natural predators allows more COTS larvae to survive to adulthood, leading to population explosions. This theory is further supported by recent evidence, including the detection of COTS eDNA in the gut contents of predatory fish, as well as higher densities of COTS observed on reefs where fishing is permitted.

The juveniles-in-waiting hypothesis

However, recent studies on the early herbivorous juvenile stage of COTS in 2020, have revealed the probable existence of a third category - the “juveniles-in-waiting hypothesis”. This hypothesis suggests that the lengthy herbivorous phase of juvenile COTS, lasting at least 6.5 years, allows juveniles to accumulate within reef structures over multiple recruitment events. These juveniles form a “hidden army” that may emerge in pulses when conditions are favourable, acting as a direct source of outbreaks. Besides, the reproductive behaviour of COTS may significantly heighten their outbreak potential. Female COTS can release up to 65 million eggs in a single spawning season, with spawning events triggered by elevated water temperatures. This exceptionally high fecundity means that even minor increases in larval survival can lead to rapid population growth, accelerating the onset of outbreaks.

All together, COTS’ biological traits including high fecundity, dietary flexibility, and adaptable growth rates create a potent combination that naturally fuels the species’ boom-and-bust cycles. These characteristics, when coupled with environmental influences, indicate that COTS outbreaks are likely the result of a complex interplay between anthropogenic and natural factors.

Monitoring COTS outbreak

COTS outbreaks are defined and monitored differently across countries depending on ecological conditions, reef sensitivity, and available resources. Each nation adopts specific thresholds and methodologies to detect and manage outbreaks effectively. In Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, an outbreak is declared when manta tow surveys detect more than one COTS per tow or densities exceed 15 individuals per hectare. Australia employs high-frequency monitoring, including robotic interventions and coordinated large-scale management. In the Philippines, an outbreak threshold is set at more than 0.25 COTS per 100 m², with belt transect methods and local community collaboration used to assess impacts linked to nutrient runoff. Guam defines outbreaks in the range of 0.22 to 1 COTS per tow, using belt transects and long swims, supported by early warning systems and community involvement. The Cook Islands use a 20-COTS threshold in designated areas, relying on visual surveys and manual collection through long swims and spot checks. Japan, especially in Okinawa, lacks a standardised threshold due to high coral diversity and instead relies on manta tow surveys, transect counts, and reports from local dive operators. Indonesia defines outbreak thresholds locally, conducting manta tow and transect surveys combined with community-led removal efforts. In Malaysia, outbreaks are defined at densities over 0.2 COTS per 100 m², with belt transects incorporated into marine park monitoring frameworks. Seychelles reports outbreaks when densities exceed 15 COTS per hectare, using spot checks and transect surveys, and employs both physical and chemical removal methods with a focus on ecologically and economically valuable reefs. Finally, Fiji considers outbreaks to occur when 10 or more COTS are observed in any reef area, prioritising monitoring in reefs frequented by the tourism sector and supporting reporting through community engagement. These region-specific approaches reflect a growing global emphasis on proactive, science-based, and participatory management of COTS outbreaks.

The Mauritian context

For Mauritius, a national protocol for monitoring and control of COTS population was developped by the Ministry of Agro-Industry, Food Security, Blue Economy and Fisheries (previously the Ministry of Blue Economy, Marine Resources, Fisheries and Shipping), through the Albion Fisheries Research Centre (AFRC) and the Coral Reef Network (CRN). The protocol, grounded in scientific literature and successful regional practices, was successfully implemented from 2021 to 2023 by Reef Conservation where vinegar (acetic acid) injections were used to safely and effectively reduce COTS densities without harming surrounding marine life. The protocol defines an outbreak as a density exceeding 5 COTS per 45-minute dive/snorkel survey, triggering immediate control measures. It outlines standard monitoring procedures using belt transects and timed dives, and prescribes injection of each COTS with 20 mL of diluted acetic acid at the base of separate arms. The control procedure is to be carried out only during daylight hours and must be followed by post-control monitoring after 24–48 hours and one week. Repeat interventions are required until densities drop below two individuals per 45-minute survey.

The COTS National Project

Coral Garden Conservation (CGC) has been officially awarded a national contract by the Ministry of Agro-Industry, Food Security and Blue Economy – Blue Economy and Fisheries Division for the implementation of a year-long project entitled “Control of Population Outbreak of Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS) around Mauritius” (Contract Ref: MOBE/Q10/2024-25/OAB1). This initiative forms part of the national strategy to safeguard coral reef ecosystems from the destructive impact of COTS outbreaks — an ecological threat that significantly contributes to reef degradation when starfish populations surge beyond natural levels. Under this contract, CGC will lead a comprehensive response that includes site-based assessments to map and monitor the distribution of COTS, the deployment of trained teams for the targeted control of COTS using safe injection-based techniques, and active collaboration with key coastal stakeholders such as hotels, NGOs, dive centres, and boat operators. The project also focuses on building local capacity through training and awareness initiatives, the development of a national COTS sighting reporting platform to facilitate real-time data collection, and fostering community engagement in marine conservation. This national effort underscores CGC’s long-standing commitment to protecting the marine biodiversity of Mauritius through science-driven, inclusive, and sustainable conservation practices.

How You Can Help

Public involvement is critical to the success of the national COTS control effort. Anyone using the sea—whether snorkellers, divers, boat operators, hoteliers, or local fishers—can play a key role in early detection and reporting. CGC has launched a dedicated online reporting platform where users can log COTS sightings, upload photos, and provide GPS coordinates. This real-time information helps our response teams prioritise and act quickly.

If you encounter COTS or signs of coral damage, please report it via the Online COTS Reporting Form, email us at projectassistantcgc@gmail.com, or call +230 5764 8502.

You can also support by sharing information with others, participating in training workshops, or volunteering for reef clean-ups.

📩 To report a COTS sighting or outbreak, click here to access the reporting platform.

Do’s and Don’ts when you spot a Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS)

Protect yourself, others, and the reef by following these guidelines:

- Report the sighting immediately to us

- Record the location using GPS, or describe the nearest landmark or reef zone where the starfish was spotted

- Take clear photos or videos, if possible, to assist with confirmation and response planning.

- Note key details, such as the number of COTS seen, approximate size, depth, coral damage, or feeding activity.

- Alert nearby boat operators, divers, or hotel staff, especially in known outbreak areas.

- Encourage others to report sightings, and spread awareness on why controlling COTS matters.

- Observe safely from a distance, especially if untrained — COTS have venomous spines.

- Do not touch or handle COTS — their spines can cause painful stings and serious injuries.

- Do not attempt to kill or remove COTS yourself, unless you are trained and authorised under the national control protocol.

- Do not leave COTS on beaches or rocks — they may survive or wash back into the lagoon, worsening the problem.

- Do not underestimate a small number of COTS — early detection is key to preventing an outbreak.

- Do not spread misinformation — always rely on verified guidance from CGC or the Ministry of Blue Economy.

- Do not damage coral or marine life while observing or photographing COTS.

Remember: Early reporting can prevent serious reef damage. Your action makes a difference in protecting Mauritius' coral reefs!